Knowledge Management History: Why Businesses Took 50 Years to Adopt It

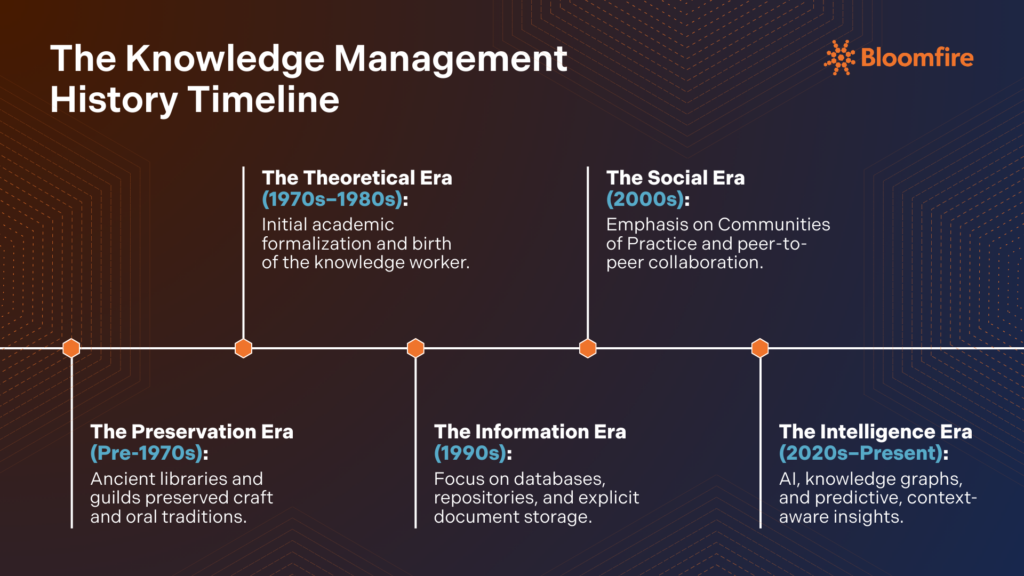

Knowledge management has deeper roots than most people realize. While McKinsey coined the term in its modern context in an internal study on information handling and use in 1987, the history of knowledge management actually stretches back further. The foundations of this field were laid in the 1970s by management experts Peter Drucker and Paul Strassman, who first began treating information and human expertise as formal corporate assets.

Some organizations saw it as a sudden breakthrough. The concept quickly caught on, and most companies showed keen interest in this emerging field by the late 1980s. The 1990s saw this concept become standard business practice. By the mid-1990s, many companies had gained a competitive advantage from their growing knowledge assets. The story behind this concept’s slow path to widespread adoption, despite its clear benefits, offers fascinating insights.

Learn more about the knowledge management timeline to understand how the discipline evolved through time and where it’s heading today.

The Preservation Era: From Oral Traditions to Alexandria

Humans recognized the value of preserving and sharing knowledge long before digital databases existed. Our ancestors’ basic need to share wisdom across generations marked the beginning of knowledge management‘s experience.

Storytelling and oral transmission in ancient societies

Ancient civilizations depended on oral traditions to preserve their collective memory. These traditions covered proverbs, riddles, tales, legends, myths, songs, and dramatic performances.

North America’s Aboriginal societies used oral traditions to transmit, preserve, and pass down knowledge from generation to generation. These communities had specialized individuals–often called walking libraries–who memorized huge amounts of cultural knowledge.

Oral narratives didn’t need exact repetition. They just needed to convey the same message. This made oral tradition a collective effort, with no single narrator controlling the stories. The landscape itself played a vital role by linking oral histories to real-life experiences.

Libraries and record-keeping in early civilizations

Knowledge management’s progress accelerated when writing systems developed. Record-keeping began in Mesopotamia around 8000 BCE, about 4,000 years before writing. Clay tokens that represented agricultural products helped people remember more than their natural memory allowed.

More complex societies needed formal knowledge repositories. Later, more advanced collections emerged, including:

- The Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh (7th century BCE), with about 30,000 texts

- Early Chinese imperial libraries that had systematic classification schemes

- Greek temple libraries and philosophical school collections

The Library of Alexandria, established around 300 BCE, stands as the crowning achievement in the preservation of ancient knowledge. It housed an estimated 40,000 to 400,000 papyrus scrolls and represented humanity’s first attempt to collect universal knowledge. Scholars hired by the library developed new ways to organize information, pioneered textual criticism, and saved countless works.

Record-keeping definition in the history of knowledge management

Record-keeping has always meant saving information beyond immediate needs throughout history. Records emerged from specific social contexts and enabled the development of large-scale, organized social structures.

They helped societies extend memory beyond individual lifespans, build knowledge across generations, and handle increasingly complex social structures. This foundational history of knowledge management shows how record-making evolved into record-keeping as societies recognized the value of preserving information over longer periods.

When considering the record-keeping definition world history provides, it is clear that these systems were not just about documentation. They were the first structured attempts to turn temporary data into permanent institutional memory.

People have always tried to capture and share what they know. Nevertheless, it would take centuries more for formal knowledge management as a discipline to take root in the corporate and academic worlds. This evolution reflects a journey from simple storytelling and libraries to the complex, AI-driven ecosystems we use today.

The Theoretical Era: The Birth of Knowledge Management as a Discipline (1970s–1980s)

Ancient civilizations relied on oral traditions and libraries to preserve knowledge until the formal discipline of knowledge management emerged during the 1970s–1980s. When examining the history of knowledge management, it becomes clear that the field has evolved from physical scrolls and archives to sophisticated digital frameworks that organize human expertise today.

Peter Drucker and the rise of the knowledge worker

Peter Drucker brought knowledge work into focus through his 1959 book “The Landmarks of Tomorrow.” He later coined the term knowledge worker in “The Effective Executive” (1966). His prediction stood out: the most valuable asset of a 21st-century institution will be its knowledge workers and their productivity. These professionals used the theoretical and analytical knowledge they gained through formal education.

Early KM systems: Augment and expert systems

This era saw the birth of the first real KM technologies. Doug Engelbart created “Augment” in 1978, an early hypertext/groupware application system. Rob Acksyn and Don McCraken developed their knowledge management system before the World Wide Web existed. Expert systems (ES) marked another early venture into commercial artificial intelligence. These systems became outdated between 1987 and 1992.

Why businesses ignored early KM signals

Businesses recognized the competitive value of knowledge by the 1980s, but widespread adoption remained slow. User resistance, developer retention challenges, and changing organizational priorities created significant roadblocks. The workplace culture made things worse. Employees hoarded knowledge to protect their jobs, while the not-invented-here syndrome prevented successful implementation.

The Information Era: KM Becomes a Business Imperative (1990s)

The 1990s brought a dramatic change as knowledge management evolved from theory to practice. Knowledge management saw limited adoption in the previous decade, but 1995 marked a turning point when management teams began paying attention.

The Knowledge-Creating Company and Japanese influence

Nonaka and Takeuchi’s publication of The Knowledge-Creating Company in 1995 revolutionized organizational perspectives on knowledge creation. Their SECI Model (socialization, externalization, combination, internalization) resonated strongly with the knowledge management community.

Many consider Ikujiro Nonaka the father of knowledge management. His theories, though rooted in Japanese companies, proved valuable across all cultures. Western management circles first noticed his work through Harvard Business Review articles published from 1986.

Consulting firms and the KM boom

Knowledge-intensive sectors quickly adopted formal KM programs. Major consulting firms such as Ernst & Young, Arthur Anderson, and Booz-Allen & Hamilton generated substantial revenue from knowledge management projects. These firms showcased their internal KM programs as success stories and actively promoted knowledge management as a strategic asset.

KM adoption in Fortune 500 companies

By the mid-1990s, leading global companies recognized knowledge management as crucial to success. Organizations such as Xerox, Microsoft, Nokia, and the World Bank have transformed through KM implementation. This era saw the rise of new KM-specific roles, especially the Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO) position. CKOs took charge of managing intellectual capital, establishing knowledge practices, and creating inventories of organizational knowledge.

Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO) and strategic KM roles

Organizations started recognizing knowledge as a strategic asset, making the CKO role more important. These executives typically earn between USD 159,000 and 277,000 annually. Their responsibilities include developing knowledge strategies, enabling collaboration, managing intellectual property, and measuring the impact of KM on business performance.

The Social Era and the Rise of Collaborative KM (2000s)

Digital technology changed how we manage knowledge dramatically at the start of the 2000s. As businesses grappled with the explosion of information and the increasing complexity of their operations, they began to recognize the strategic importance of leveraging their collective knowledge. Early efforts focused on codifying best practices and creating databases to store information.

Intranets, wikis, and knowledge repositories

Information sharing changed forever with the Internet revolution. Organizations started using centralized knowledge repositories to curb inefficiency. Employees previously lost approximately 1.8 hours daily searching for information.

Fortune 500 companies wasted a staggering USD 31.50 billion annually because of this inefficiency. New collaborative platforms emerged as a solution. Intranets worked as private networks for internal communication, while wikis let multiple users edit shared knowledge bases.

KM lifecycle: create, store, share, unlearn

The modern development of knowledge management has resulted in a refined cycle consisting of four connected stages: create, store, share, and unlearn. Companies that used this well-laid-out approach saw productivity improvements of up to 25%.

Knowledge creation starts the process, followed by capturing tacit knowledge, which accounts for 80-90% of organizational knowledge. Storage systems grew from basic databases into sophisticated repositories with metadata tagging and version control. Knowledge distribution happens through both push and pull models, finally.

Communities of Practice (CoPs) and the Web 2.0 revolution

The mid-2000s marked a pivot from knowledge management as a library to knowledge management as a conversation. This era was defined by the integration of Web 2.0 technologies—social tools that prioritized user-generated content and peer-to-peer interaction. Instead of waiting for a central authority to publish official manuals, employees began using internal blogs, discussion forums, and tagging systems to curate information in real-time.

Central to this social revolution was the formalization of Communities of Practice (CoPs). These are self-organizing groups of experts and practitioners who collaborate to solve recurring problems. This shift transformed KM from a top-down administrative task into a bottom-up, organic movement, fostering a culture in which sharing knowledge became a social norm rather than a formal requirement.

The Intelligence Era: The Evolution of KM in the Digital Age (2020s)

Artificial intelligence is reshaping knowledge management by automating processes and identifying connections between seemingly unrelated information. Remote work has accelerated KM adoption, necessitating resilient systems to enable smooth knowledge sharing across distributed teams.

The KM evolution culminates in the rise of Enterprise Intelligence, where the focus shifts from merely capturing and storing data to generating actionable, context-aware insights across the entire organization. Unlike traditional KM, which often relied on manual tagging and siloed repositories, Enterprise Intelligence leverages a knowledge graph architecture to link structured data with unstructured human expertise.

Enterprise Intelligence creates a living ecosystem where the system not only knows facts but also understands the relationships among projects, skills, and market trends. By integrating machine learning with collective human experience, organizations can move beyond retrospective reporting toward predictive decision-making, ensuring that the right intelligence reaches the right person before they even realize they need it.

Why Knowledge Management Took So Long to Formalize

Knowledge management has ancient roots, yet organizations have struggled to adopt this formal discipline. The evolution of knowledge management as a strategic business function was not immediate; the gap between its concept and widespread use spanned half a century driven by three main challenges: technological limitations, organizational silos, and the difficulty of capturing tacit expertise.

Tacit vs. explicit knowledge: the core challenge

The biggest problem in knowledge management comes from two distinct types of knowledge: tacit and explicit. Tacit knowledge lives inside people’s minds. It comes from personal experience and specific situations, making it difficult to express. A significant fraction of tacit knowledge disappears within six months of an employee’s departure. Explicit knowledge, while easy to document, represents the tip of the iceberg in an organization’s knowledge ecosystem.

Lack of technology to share knowledge flexibly

The first types of knowledge management systems were clunky and hard to use. Users had to stop work, switch between apps, and navigate complex categories. These technical hurdles created resistance, and people viewed knowledge sharing as extra work rather than helpful. Many companies also lacked the money and IT skills to build systems that work.

Cultural resistance to knowledge transparency

The most pressing issue was how people held onto their knowledge. Workers often saw their expertise as a form of job protection. This created environments where information became a powerful tool rather than a shared resource. Such attitudes blocked the free flow of information. These cultural roadblocks remained unless leadership actively promoted knowledge-sharing values.

From Ancient Roots to Dynamic Ecosystems

Knowledge management isn’t a newfangled concept. Humans have always sought to capture and share what they know. However, the formalization of KM as a discipline took root in the late 20th century. Today, KM is about creating a dynamic ecosystem where information flows freely, empowering organizations to adapt, innovate, and thrive. It’s less about static repositories and more about building a culture of continuous learning and knowledge sharing.

By the late 1990s, organizations realized that technology alone wasn’t enough; people weren’t sharing their knowledge. This led to Generation 2, which focused on culture, Communities of Practice (CoPs), and human behavior rather than just database storage.

CoPs were popularized by Etienne Wenger in the late 1990s. Historically, they replaced rigid hierarchical reporting structures with social networks of experts who voluntarily shared knowledge because they faced similar professional challenges.

The history of KM is a journey from storing (archives/libraries) to connecting (intranets/social KM) to predicting. Today’s “Enterprise Intelligence” is the direct descendant of KM, using AI to automate the connections that humans used to have to make manually.

The pandemic served as a massive accelerant. It forced companies to abandon physical filing and water-cooler knowledge sharing, leading to a rapid adoption of digital “knowledge ecosystems” that support distributed, asynchronous work.

Today, we are in the era of Cognitive KM or Enterprise Intelligence. AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) are used to tag content automatically, summarize vast amounts of data, and provide just-in-time knowledge to employees.

The ISO 30401:2018 was the first international standard for Knowledge Management Systems. Its release marked a major milestone, providing a globally recognized framework for what constitutes a high-quality KM program.

How to Improve Customer Service: 9 Strategies to Automate Success

7 Best Customer Service Knowledge Management Systems in 2026

The 6 Knowledge Management Trends That Redefine Strategic Intelligence in 2026

Estimate the Value of Your Knowledge Assets

Use this calculator to see how enterprise intelligence can impact your bottom line. Choose areas of focus, and see tailored calculations that will give you a tangible ROI.

Take a self guided Tour

See Bloomfire in action across several potential configurations. Imagine the potential of your team when they stop searching and start finding critical knowledge.